Thinking about parenting

A guide to leading change and supporting whānau to move towards conscious parenting using 'Thinking about parenting' and other Tākai booklets.

Parenting is one of the most rewarding and challenging jobs there is. However, children don’t come with instructions. Parents need support and encouragement in this valuable role.

Our booklet 'Thinking about Parenting' is an easy-to-use resource that was developed to support parents and caregivers with their parenting. It’s based on the Tākai booklet Conscious parenting: A resource for use by supporters of parents — Module one. Module one is further supported by Child development and behaviour — Module two, and The six principles of effective discipline — Module three.

The 'Thinking about Parenting' booklet promotes reflection, thinking about the child’s future, and through discussion, supports parents and caregivers to think about:

- how they want to parent their child

- how they interact with and manage their child now

- how this might feel to the child

- how to change what they’re doing so that their child has positive memories about their early life and grows up to be a happy and capable adult.

Supporting conscious parenting

The supporting information on this page will help you make the best use of the 'Thinking about Parenting' booklet and other resources. These resources give ideas and prompts to help parents become more conscious of their parenting. For example:

- ‘We all want the best for our kids’ ('Thinking about Parenting', page 2).

- ‘…what happens in families during childhood has a lifelong effect on children’s happiness and success’ ('The discipline and guidance of children', page 4).

- When you think about your childhood, what do you remember? Do you recall:

- happy memories and experiences?

- unhappy memories and experiences?

- As you think about your childhood are there things that you wish hadn’t happened or that you wish had happened more often?

Often parents and caregivers will carry what happened in their own childhoods through into their own families. Most parents will instinctively and unconsciously behave in the same way that their parents or caregivers did. If this wasn’t a good experience, then they may want to change the way they behave towards their own children.

The conversation prompts in 'Thinking about Parenting' (page 2) will help parents to reflect on how it felt to be a child on the receiving end of their parents’ parenting skills. Have they heard themselves saying the same things that their parents said to them, and does this make them think or say, ‘I never wanted to sound like that!’?

When a parent writes down something that they want to carry forward, that they want their child to remember, this helps to make it real – a goal to work towards, an outcome to ‘see’ for the future.

Likewise, when a parent writes down something that they don’t want to carry forward, then this helps them to be determined to do things differently. A likely long-term outcome will be that their children and grandchildren will have better experiences and memories of how they were parented. The parent will be changing a ‘cycle of behaviour’.

When parents make deliberate and intentional decisions about how they want to parent their child, they’re practising ‘conscious parenting’.

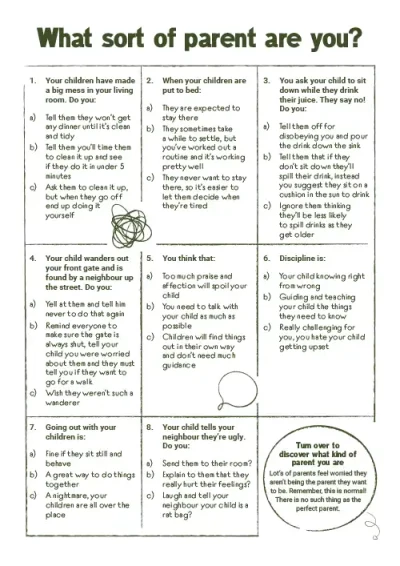

‘Everyone has their own style of parenting’

('Thinking about parenting', page 3)

The terms used here for the different parenting styles are:

- The rock

- The tree

- The paper

You may have already read about parenting styles as ‘authoritarian’, ‘authoritative’ and ‘permissive’ (Diana Baumrind, 1966). These terms are quite technical and not so easy to understand. The terms ‘rock’, ‘tree’ and ‘paper’ give us a good picture of the behaviours used by parents that make up each style of parenting.

Parenting style and likely parental behaviours

|

The rock (authoritarian) Also known as ‘brick wall’ |

The tree (authoritative) Also known as ‘backbone’* |

The paper (permissive) Also known as ‘jellyfish’ |

|

Strict rules – rigidly enforced |

Firm setting of and sticking to limits |

Lack of boundaries or limits |

|

Unquestioning obedience – no choices given |

Allow children freedom while setting clear standards for behaviour |

Avoid conflict at all costs – especially if the child is getting upset |

|

Emphasises respect for authority – without giving reasons or showing understanding |

Use reason and listen to the views of children |

Tend to ‘rescue’ children – child has little chance to think things through for themself, or to experience disappointment or ‘failure’ |

* The terms ‘brick wall’, ‘backbone’ and ‘jellyfish’ are used by Barbara Coloroso in her teaching about parenting styles.

When we consider how these behaviours affect children, we can see how each child’s development, character and behaviours are shaped by their parents’ parenting style.

Parenting style and children’s likely behaviours

|

The rock (authoritarian) |

The tree (authoritative) |

The paper (permissive) |

|

Increasingly passive |

Self-motivated |

Less able to tolerate frustration |

|

Doubt own abilities |

Have developed self (internal) discipline |

Insecure and overly dependent |

|

Slow in building self-confidence |

Have good self-esteem |

Slower in making decisions |

|

Slow in building resilience – haven’t learned how to deal with ‘failure’ |

Know what they want and how to get it |

Slower to develop their problem-solving ability and persistence |

|

Likely to feel conditionally loved |

Respectful of others |

Unaware of how their actions affect others |

Many parents will operate in more than one style, depending on other factors in their lives. These include tiredness, the amount of support they’re getting, and the level of stress and number of stressors they’re experiencing.

Helping parents to think about how they ‘mostly’ behave may encourage them to plan how to parent their child more effectively.

Download 'Conscious parenting – Module one' for more on parenting styles [PDF, 839 KB]

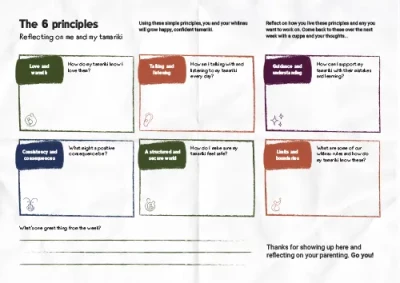

‘What does fair and firm parenting look like?’

('Thinking about Parenting', page 4)

Looking back at page 3 of the booklet, we’ve already identified some of the parenting behaviours that sit within particular styles – the ‘rock’, ‘tree’ and ‘paper’. So where does ‘firm and fair’ parenting fit? Typical ‘tree’ parenting behaviours are:

- setting firm limits and sticking to them, but also letting children have some freedom in their behaviour (while still ensuring that they know about what’s ‘okay’)

- using reason and listening to their children’s views; being sensitive to their children’s needs and views

- using praise and making their expectations clear.

Suggestions for being a ‘tree’ parent

There are a few simple suggestions offered in 'Thinking about Parenting' (page 4) that fit well with the ‘tree’ style of parenting.

Limiting the number of rules will help parents to consistently stick to them, and make it possible for their child to remember them.

Having reasonable expectations of their child means parents need to know what ‘normal’ behaviour is for their child’s stage of development.

When the parent expects their child to behave in a way that would be ‘normal’ for a child 2–3 years older, then the parent will likely feel frustrated, disappointed and possibly angry. The child may feel bewildered, hurt and distressed.

To help keep parent expectations realistic, use the child development parenting resources in this resource, and the Tākai booklet 'Child development and behaviour' – Module two.

Note: the term ‘normal’ means that certain behaviours and levels of development are seen in most children of a similar age or stage. If children seem to be more advanced or delayed in development or with their behaviour, then take a closer look. You may need to refer the family to other service specialists and plan carefully to ensure that the child and parents’ needs are being met.

‘Things to think about and try’

('Thinking about Parenting', pages 5 and 6)

There will be plenty of times when ‘the going gets tough’. As children grow and develop, they’re bound to stretch the limits and boundaries that their parents have set – curiosity is all about learning. Needing to ‘go further’ (push boundaries) is about building capability and confidence, and learning from observations about how people behave, react or respond.

During home visits with the whānau, there may be many examples that parents share about what their children are doing. New or different child behaviours, expectations and circumstances will need thinking about. Parents will have ideas about what’s okay and how they want their children to behave.

Parents will also have heard many comments that seem ‘correct’ and ‘okay’ – but are they really? Here are some examples that might come up in conversations:

- ‘It’s my child and I have the right to choose how I parent.’

Children are individuals with the same rights as their parents. It’s the parents’ role to protect their child and raise them to be happy, capable adults. It’s the parents’ right to choose how they parent – as long as they don’t harm their child.

- ‘I was smacked and it never did me any harm/hurt me.’

Smacking isn’t always harmful, but it doesn’t teach a child what to do, and can make them feel rejected and unloved. Abuse is frequently the result of harsh or physical punishment that escalates into violence. Smacking is illegal – we need to use other ways to manage unacceptable behaviour. Even more importantly, we need to understand what’s causing the behaviour in the first place.

- ‘If you don’t take control, your kids will control you.’

Children do need to have structure, limits and boundaries so they feel secure and learn to manage their own behaviour. However, this doesn’t mean ‘control’ – it means having a few important rules that everyone understands and sticks to.

‘Fair and firm parenting’ involves thinking about what’s happening, why it’s happening, how the child is feeling and how the adult is feeling. What else might be causing these behaviours?

In 'Thinking about Parenting', pages 5 and 6 offer ideas, tips and things to think about. If we think about how we would feel if someone treated us in a particular way, then isn’t it likely that a child would feel the same?

Sometimes breaking parenting challenges down into individual pieces can help parents work through them. There are a number of problem solving models around, below is a ‘six step’ model which might help parents who are feeling overwhelmed by their children’s behaviour.

Step 1: Identify the problem

Think about what’s happening, when it’s happening, who’s involved and what they’re doing. Ideally, everyone involved has a chance to talk about the problem, and how they feel and what they think. However, with small children this often isn’t possible –so parents need to think about the problem from the child’s point of view too.

Step 2: List the possible solutions

Brainstorm all the possible solutions and write them down. What might help to solve the problem?

Step 3: Take a closer look at the possible solutions

Think about the advantages and disadvantages of the solutions, and what might happen if each solution is tried.

Step 4: Choose a solution to try

Rank the solutions from the ‘most likely to succeed’ to the ‘least likely to succeed’, and choose one to put into action. Are any of the solutions ‘way out there’ or completely impractical?

Step 5: Enact the solution

Work out how to carry out the solution and who else needs to know about what you’re going to do, so they can help with a consistent response. Parents (and wider whānau) need to agree about what they’re going to do. Decide when you’re going to start and when you will review how well the solution is working.

Step 6: Think about whether it worked

Decide whether the solution worked – were there any unexpected consequences, and have these new behaviours become a problem? If yes, then go back to Step 1 again.

This kind of approach needs consistency and enough time to be effective. Step 6 might need to be repeated several times to get the desired result: a parent and child working together for the best possible outcome for the child.

‘5 stages of change’

Tākai research identified 5 stages of parents becoming ‘conscious’ about their parenting practices. ‘Thinking about parenting’ and ‘trying different strategies’ sit right in the centre of the ‘spiral of learning’. The 5 stages of becoming conscious parents include:

Stage 1: Unaware

Stage 2: Becoming aware

Stage 3: Ready to change

Stage 4: Taking action

Stage 5: Maintaining change

Parents move through the stages at different times, in different ways, on different matters. Ideally, they’re continually identifying areas in their parenting that they haven’t been aware of, and making decisions about what practices they want to keep and what they want to change.

To learn more about the ‘5 stages of change’, see 'Conscious parenting' – Module one, page 7.

‘Children are born to learn’

('Thinking about Parenting', page 7)

Keep looking through the child development information, play activities, songs and rhymes in this resource. You’ll find many new topics to discuss and activities to try with whānau.

Children often want to do the same activities, games and songs over and over. This is usually because they:

- Enjoy them

- Know them (and can remember how they go)

- Feel confident with them

- Are curious about them

- Want to find a different way to use them

- Want to see how they work

- Want to see how to change them

It’s numbers 4–7 that can get children into trouble, especially as their skills develop. They can reach higher, are stronger or can use those little fingers to take things apart.

Adults who help children’s early development are:

- ‘warm’

- take notice

- are patient, responsive and sensitive

- listen, talk and have time.

Singing, caring, smiling, hugging and being enthusiastic all make any learning experience fun.

Adults who take an active interest in their child’s activities and who introduce varied, suitable play and toys, will help their child’s development. Adults also have a role in linking children’s knowledge to familiar and unfamiliar (but similar) things.

‘Avoiding problems before they start’

('Thinking about Parenting', pages 8 and 9)

When parents are aware of what their children are doing, or are about to do, it’s easier to act quickly and distract children from exploring places and things that are not suitable or are dangerous. Putting precious or dangerous things away, up higher or making them safe will make their home a safe, child-friendly place.

Doing a ‘crawl’ with the parents around the family home will most likely identify quite a few danger spots – dangerous for the crawling or toddling child (or ‘dangerous’ for the precious things). Making the home safe and child-friendly will mean that many potential problems won’t even arise.

However, the family home isn’t the only place to consider safety – a few other examples of experiences that parents and children have almost every day include:

- visiting friends and family

- going shopping

- getting in and out of the car

- going for a walk

- riding on the bus.

Planning ahead makes life easier for everyone. The information in 'Thinking about Parenting' on pages 8 and 9 can help start some good conversations with parents. The Whakatipu and other Tākai booklets ('Tips for babies', 'Tips for under-fives', 'The tricky bits and Staying calm with kids') will be useful during these conversations too.

‘Parents make mistakes too’

('Thinking about Parenting', pages 10 and 11)

There will be times when parents ‘lose it’, or say and do things with or in front of their children that later they’ll wish they hadn’t. The best thing to do is make sure their child is safe, go somewhere to calm down, figure out what went wrong and then go and ‘make up’. Saying ‘sorry’ and showing that they love their child is modelling appropriate behaviour that the child will, in time, learn to use themselves.

Making changes takes time – when parents start parenting more consciously, there will be times when old behaviours slip in. There might be some going back and forward too, with some behaviour changes more successful than others. Behaviours that are more ingrained will be harder to change and may take longer to change, but are not impossible to change.

When unwanted behaviour slips back in, encourage parents to:

- think about what did or didn’t happen

- don’t give up, just get started again

- look at what they’ve achieved or changed, and the successes they can celebrate.

Resistance to change

It’s useful to understand that new ideas, new ways of talking with children and a new focus on supporting children (rather than punishing them) can all meet resistance – not only from the parent, but also from the closer or wider whānau. This resistance to change usually eases off as the benefits for everyone, especially the parent and child, become more apparent.

As parents realise that they can do things differently, their confidence builds and they start to believe that they can be successful in changing their behaviour. ‘Self-efficacy’ is essential to progress (Tākai research report). Parents need to know that they’re doing well, so be sure to compliment them on their progress. Having their successes acknowledged by someone else will help them to believe in themselves as their child’s first and most important teacher.

Helping parents to identify their current strengths and think about new strengths that they’d like to strive for is a useful way to celebrate their successes and set some new goals.

Conscious parenting is about making thoughtful and intentional decisions on what outcomes parents want for their children. It’s also about the atmosphere and feelings that parents want to create within their family. You can support them to achieve these outcomes.

Learn more

Barbara Coloroso: Changing parenting styles

YouTube

Barbara Coloroso (2001): Kids are worth it: Raising resilient, responsible, compassionate kids. Penguin, Canada. (Book)

Barbara Coloroso: More parenting tips

YouTube

Tākai research report undertaken by Gravitas (DOC, 288 KB)

Ministry of Social Development

This report informed the development of Tākai, previously SKIP.

Three research reports on Māori child-rearing practices

Mana ririki

Parenting techniques

Mana ririki

Parenting with passion: Barbara Coloroso shares her critical life messages

YouTube

Diana Baumrind’s (1966) Prototypical descriptions of 3 parenting styles

DevPsy.org

A theology of children - Reverend Nove Vailaau explores what the bible says about raising children

Pasifika Proud

Traditional Māori Parenting – An Historical Review

Mana ririki

Professor Kuni Jenkins, PhD. Helen Mountain Harte M.A. – Te Kahui Mana Ririki.

Beliefs about tamariki

Mana ririki

pdf 4.6 MB

pdf 4.6 MB