What do kids need when a relationship ends?

Children can feel helpless when parents separate. Parents need to work together to prioritise their wellbeing, maintain contact and reassure them of their love.

When a couple decide to end their relationship, the impact reaches wider than the two of them. The ripple effect touches all their friends and whānau, and none more so than their kids.

How are the kids feeling?

When their parents separate, younger tamariki might be aware that something has changed, but they may have difficulty understanding what exactly has happened. Their older siblings, like their parents, will experience a range of emotions. Initially this may be shock or disbelief, and then maybe anger and sadness as they realise the finality of the situation.

The older children can also feel somewhat helpless as their life changes around them and they have no control over it.

Breaking up can be hard for everyone

Having a close and loving relationship is a great source of emotional, social and practical support. So when a partnership falls apart, the loss of these supports can make life feel very hard at times. And again, that’s not just for the couple but for their tamariki too.

A relationship split can be the cause of a lot of worry and stress, and the problems associated with their parents’ breakup can have ongoing and sometimes long-term effects for kids. That’s why it’s so important to prioritise their wellbeing during any relationship split.

How children might respond

Children’s behaviour might also add to their parents’ stress levels as they try to make sense of the breakup. The big emotions that they’re dealing with might be seen in physical ways, like a regression in toileting, an increase in bedwetting and nightmares, more hitting or fighting, and being wakeful during the night or hard to settle to sleep.

Some kids may be needier – for example, not wanting to go to Early Learning Service or complaining of various ailments like a ‘sore tummy’. Some will be anxious or have scary thoughts, and some tamariki can even feel guilty that they’ve done something to cause the split.

Older kids may challenge the boundaries set by parents. They may be angry, sad or rude, not eat well, have trouble at school and make bad or dangerous choices with their peers.

Responding to these behaviours with understanding and empathy will help, even though it may be very difficult – especially as parents may be dealing with their own big emotions.

Finding help

Seeking out the right type of help for each family member is important. Parents might make a time to speak with teachers at their child’s daycare or school. They can let them know about the changes that are happening within the whānau, and if there are any concerns about the child’s behaviour, they can work together on ways to help.

If there are worries over children’s emotional health, teachers may also have contacts for local support services for tamariki. If necessary, help parents to access helplines, child counsellors or family therapists who are trained to work with children and their parents.

Children may feel that everything will be okay if only their parents would get back together. It’s vital to help them understand that this is unlikely to happen, without putting the other parent down.

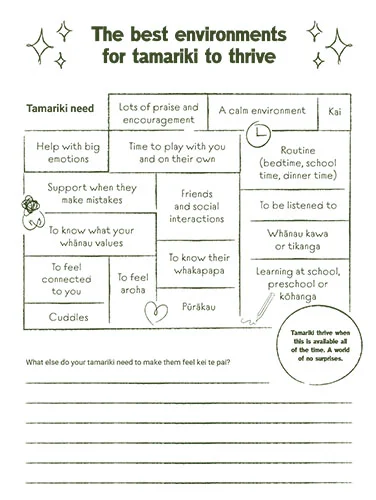

What do children need?

Children need their parents working together to help them through the split and firstly asking themselves, “What’s best for our kids?” It’s overly optimistic to expect tamariki to cope with the breakup changes when their parents aren’t coping well with their own emotions.

Grilling kids or trying to elicit information about the other parent can put added pressure on them that they don’t need. What they do need is their parents acting in an adult way. They need assurance that they remain a family, even though they’re not living together as they once did, and that their parents still love them and want them to feel okay.

Research confirms that keeping in touch regularly is the key to them feeling okay, such as phone or video calls for the younger kids, and text messages or conversations via social media for older ones. This contact affirms that the parent who is away from them still cares, still thinks about them and wants to see and hear from them often.

If this type of communication is unfamiliar to a parent, they may need to find some help to upskill themselves. By doing so they show their kids how important they are to them.

Tamariki need to keep in touch with other wider family members too. They should not lose their ties with grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins just because their parents are separating. It is up to parents to work together in a positive way to help keep those ties intact. Their kids share whakapapa with these people and should always feel included and part of their extended whānau.

Coping with being physically apart from one parent

Most children want to be together with both their parents in the same place. So, if they’re living apart after a split, kids can sometimes feel guilty at enjoying being with one parent while the other is absent. This can escalate for them too if another partner enters the mix, especially if the other parent is not happy about it.

Communicating any upcoming changes to the other parent helps their tamariki so much. Openly sharing information helps to remind the kids that they’re still a whānau who talk to each other and care about each other’s lives.

Whether it’s moving house, changing jobs or introducing a new partner, anything that might cause disruption or stress for tamariki needs to be shared. Kids thrive on predictability and feel safe and secure when they know what’s happening in their lives.

And it’s the adults in their lives who can make that happen.