Webinar: Ngā tohu whānau – the 6 principles

This Tākai Kōrero webinar from 17 August 2022 features Lynette Archer, Jason Tiatia, Anna Mowat and Lily Chalmers. They discuss ngā tohu whānau – the 6 things children need to grow up to be happy and capable adults.

Watch the webinar recording

Tākai Kōrero webinar: Ngā tohu whānau – the 6 principles (transcript)

Lily Chalmers:

Ko te manu kai i te miro, nōnā te ngahere, ko te manu kai i te mātauranga, nōnā te ao. The bird that feeds on the miro berry, theirs is the forest. The bird that feeds on knowledge theirs is the world. Kia ora tātou, nau mai ki tēnei wānanga o Tākai Kōrero. Ko Lily Chalmers ahau.

Good morning, and welcome to Tākai Kōrero, our webinar Ngā Tohu Whānau: The six principles children need to grow up to be happy and capable adults. Thank you all for taking the time in your busy day to join the session, and a shout out to all those watching on Facebook live. The session will be recorded later, and we’ll be uploading it to the Tākai website.

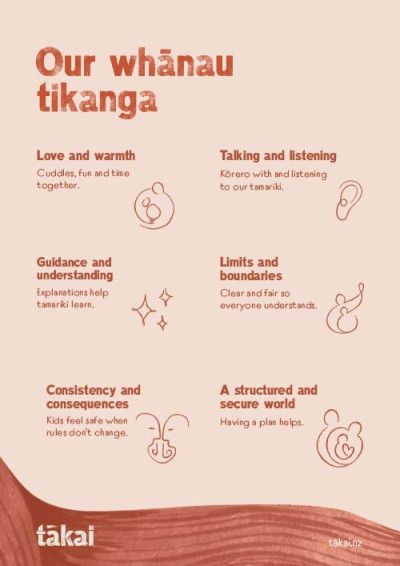

In 2004, the Children’s Issues Centre, Otago University, and the office of the Children’s Commissioner, published a research report called The Discipline and Guidance of Children which revealed six key principles for effective relationships with kids. The principles provide a foundation for managing kids behaviour, without hitting or yelling. The six principles are love and warmth, guidance and understanding, talking and listening, limits and boundaries, a safe and secure world, and consistency and consequences. Today we will chat with our kāikōrero about the six principles and how they weave there, the principles into their mahi supporting whānau. We’ll also talk about the strategies that whānau supporters might use to have conversations about conscious parenting. Now, I am going to introduce our wonderful guests for today.

First, we have Lynette Archer. Lynette is the coordinator for Woven Whānau Whanganui, an initiative funded by Tākai that was previously known as SKIP Whanganui. Lynette began walking alongside families when hosting playgroups, and has always been passionate about seeing whānau and tamariki able to be the best they can be.

Our next guest Jason Tiatia is based in Christchurch. Jason is a Brainwave Trust Aotearoa kaiako. He’s also a programme coordinator and tutor at Ara Institute of Canterbury, where he teaches sports coaching, and indigenous studies, tutors in Pacific performing arts, Gagana Samoa.

Lastly, Anna Mowat. Anna works across many initiatives, and projects that support tamariki and whānau. She’s the lead for Sparklers ‘directs real parents’, and has been using the six principles in her mahi with whānau as a parent, and as a parent for the last sixteen years. She’s clinically trained in psychology, with a predominant focus on tamariki wellbeing.

Welcome. Kia ora, and we’re going to just get straight into our questions. We’re going to talk about the evolution of the six principles, and Anna, I’d love to ask you; what do you know about this research, and how it came about?

Anna Mowat:

Kia ora Lily. So what I know about that research is as you said, it was commissioned in 2004, and it was a response to we at that time, in our law; we had what was called Section 59, or it’s still called Section 59, which meant that adults had the right to use reasonable force with children, and it was a bit of an undefined and ambiguous kind of law that meant that some children were experiencing things like being hit with sticks, and tied up to metal chairs. And so, the United Nations Conventions Rights of the Child put pressure on us, and rightly so, to change that law, and have that changed. So, thus came the reform of Section 59.

And so, what happened for parents at that time, is that while we were being told that smacking was no longer available to us as a form of discipline, or punishment. Instead, we needed something else that was available to us, and I kind of love that this research actually produced these six tohu, or principles, that parents could do. It really shaped and changed the way that we started to kind of identify, or relate to children. So, instead of smacking we had providing love and warmth, and providing guidance and understanding. So, it was that real shift in the way that we were relating to children. I do want to say though that this is a particularly colonised way of thinking about children, that had come over with us during colonisation times, in the sense that, that was the culture that was kind of immersed and the children should be seen not heard. Section 59 makes sense in that context. It doesn’t make sense in the context now, and it didn’t make sense for indigenous parenting styles. We know that Māori did not smack, or use physical harm against children.

Lily Chalmers:

Yeah, that’s awesome, and I guess it was a real spectrum before the law change, that as you say some people were tying their children up, and some people were just giving them a wee smack. So at least now we know, we have a very clear kind of guidance around none of it’s okay, and we need to find other strategies, but I just wanted to ask you a little bit about that word ‘discipline’ because it does have quite negative connotations I feel, and I think you’ve got a really good kōrero on that.

Anna Mowat:

Well, discipline at the time is a bit of a clinical term and it was used, but what’s happened is it’s become tainted. So, the word discipline comes from the word ‘disciple to teach’ or ‘to guide’ which is kind of beautiful, but it’s been kind of interspersed with the word punishment. And so, we think about discipline as being wholly negative, but I do wonder whether or not that’s strategic at the time, because we were talking about a punishment being smacking, which was interchanged with the word discipline, and I wonder whether or not they were using the term discipline, to reframe the way that we were relating to children, in terms of discipline being providing love and warmth and things like that. But I don’t think it’s quite worked, and I do think that we need to rethink it and maybe not refer to these kind of wholly positive, very relationship focused principles, and tohu as discipline. They’re ways of being, aren’t they, they’re ways of relating. They’re what we can take with us in any relationship we have, whether that be at work, with our children, or inside of our own whānau with our parents, etc.

Lily Chalmers:

Even with ourselves. Lynette and I were talking about a bit of guidance and understanding of our own selves this morning.

Lynette, tell us about that research and what Woven Whānau, or you were SKIP Whanganui back then did, because it is quite academic type research, and maybe you found a better way to reframe it. Can you tell us a little bit about how that came about?

Lynette Archer:

Sure, mōrena koutou. The research when it came out was it’s a wonderful booklet, it’s a great read but it’s wordy. And so, Janet who was the SKIP Whanganui coordinator at the time, saw that actually, the whole process was cyclical. If you began with love and warmth and you took all of the principles you came out that children felt safe and secure in their world. So what she did is she took the headings and she created a kind of circular model of it, with the child in the centre and each of the arrows pointing to the next one, with the final one saying ‘safe and secure world’, and actually, it’s not just for whānau is it. We can do it in all of our mahi alongside just people in our own families, but it certainly has changed the security a child may feel in families now that they know some of those kinder ways to support their behaviours. Yeah, so that’s kind of what it came out of here, and it got taken by SKIP, and they got very excited and it got used for many years, is that circular model that many people may remember, and then it’s been put into the ngā tohu whānau as well, which has come out, which looks a little bit different again.

Lily Chalmers:

Yes, and that’s a resource we reproduced when we relaunched Tākai in March, and you can find it in our website. It’s called Our Whānau Tikanga, and it is a really great way to start to have those conversations as a whānau, about how you’re going to deal with some of the behaviours and how you’re going to really phrase some of those behaviours and spotlight the great behaviours as well.

So, you said SKIP Whanganui came up with the cyclical model. How did that influence or change the work you were doing?

Lynette Archer:

It’s kind of guided how we would begin with parents. It gave us an idea that instead of just giving them so much information we could just take it bit by bit, and we knew that if parents got this bit well, we moved onto the next bit and they got that bit well. And we wrapped a lot of maybe workshops or opportunities to sit down and talk about how that felt for them. It was a big change, like Anna was talking about, when we repelled that Section 59. So many people said, “So what are we going to do now?” They felt like all of their what they understood in the role modelling they’d had, had gone out the window and they were left worrying about getting it wrong. So, a simple model meant that you could bring a change that was easily connected to, I think would be the best way to put it.

Lily Chalmers:

Yeah, that’s awesome, and I do still kind of hear that sometimes, “How are we expected to teach our children without smacking?” It’s like, “Well, we have a conversation.” I think that breaking it down into the six principles and going through and working with whānau to understand what they can do at each stage, is a really great way for them to come up with, and identify what they’re already doing as well isn’t it. Yeah, great.

Jason, welcome. I’ve got a question for you. We’re going to talk about how I’m linking to the six principles. I wanted to ask you, from a brain development perspective: what effect does using ngā tohu whānau have on the growing brain?

Jason Tiatia:

Talofa Lily, and kia ora koutou. Awesome, I think they all match up in terms of information goes into the brain, and obviously, with our parents and babies interacting with each other, it’s all about the serve and return effect, and that’s myelinating the brain. So, the more experiences, or rich experience we give, the touch, the feel, all the sensory experiences that we give our kids, definitely, definitely we see a better person. They enjoy life, they enjoy the relationships, even the language that we use is a one. So, I’ve been a dad myself. We’ve got three beautiful kids who are Māori descent, and also Samoan descent, and they love speaking the languages. So they have a relationship with the languages, and kids can identify that at a really young age. Their brains work amazingly, they know how to connect. So there’s these things called myelination which is repetition in the brain, and sort of helps, speeds up the process, but then there’s also there’s this part where it’s called synapses. So when there’s a connection to one neuron to the other, and it’s we always talk about the ‘lightbulb moment’. Those are the lightbulb moments that we have, and even as adults we’re like, ‘oh, I got it’, but if we do practice it every day, day in day out, there’s playing on the pots or even cooking with each other, or just playing catch pass whatever it is, those are the interactions that we really encourage, and from our Brainwave Trust.

And when going into sort of do a workshop, whether it’s in directions, or in the community with different parent groups, they can see it. They already know what they’re doing, especially with the indigenous. I’m glad you brought up the indigenous side Anna, around our Māori and Pacific have been doing these practices for years, centuries, right, and it’s the touch. We generally carry our kids around with us everywhere, and now I guess back in the day, if I knew this; I would parent differently too. I wouldn’t let my kid cry as long, because we were told that was the formula at the time with the nurses or the midwives, but research, the modern research shows if we can hold our kids, teach our kids, feel our kids in a way that’s nurturing, warmth, loving, talking and listening, that’s a massive one too for us. As Pacific, we speak a lot, and I know my mum and dad, especially my aunties, “Dah-dah-dah-dah-dah.” It’s all, and it’s rich language, and it’s something that you can’t teach in a classroom. So reading to them at night is a big one. So that communication under serve and return effect, where maybe baby’s pointing to the pictures, those sort of things, or pointing to the following the words, or even make up your own story. That’s the imaginative side, and that’s the part that we need to keep creating.

The last thing I want to share with, in terms of I guess how the parent and the child interacts with each other is around the brain stem. If you put your hand like this team, if you’re watching. So you’ve got the brain stem at the bottom, the Olympic systems in the middle, and then at the top there is the front part which is the cortex and a prefrontal cortex, and that’s the stuff we need to keep. That’s the decision making space where when we get, I guess tired, or even stressed, we tend to go back down to the brain stem which is survival, fight flight, etc. And sometimes we need to sort of practice that, understand that, and give them strategies around that too.

So if we can, generally our mothers, if our mothers are feeling stressed during their time with their babies, that’s how a baby will react too, in terms of how they stress too. So, our dads, our grandpas, our nans, our aunties, the people who are caring for our mothers out there, we need to look after them as much as we can. Give them the best care ever, and then we’ll get the best outcome for our child too, and they’ll thrive in our world. So that’s something to take into consideration. Being a Pacific person I love being a dad, honestly. I love teaching my kids, and they teach me too, “Dad, don’t do that.” I’m like, “Okay, sweet-as, yeah.” I think that’s a really good understanding of the communication of serve and return.

Lily Chalmers:

Awesome, so much there to take in actually. So, we have a baby wall frieze. I don’t know if you’ve seen it Jason, but there’s some great little guiding principles in there around the six principles, and it’s, “Read to me.” “Talk to me.” “Sing to me.” All those things. So, as you’re saying that’s creating those pathways in the brain. That communication and that talking and listening, guidance and understanding. And what I also heard from you, is that it’s really difficult to do conscious parenting when you’re having struggles. When you’re struggling or when things are stressful.

I think it’s important that we remind parents that we all have bad days and that we all make mistakes and we have to forgive ourselves and give ourselves understanding as well, and I know as a parent myself I don’t consciously parent every day, sometimes I’m just reacting, and what I try and do is say to my children, “I’m sorry, mummy’s having a hard time at the moment and I’m going to try better and I love you so much, and I’m really sorry that happened and I spoke to you that way.” I think that’s another key thing to remember is that don’t give yourself a hard time because you’re going to add more stress to yourself.

Jason Tiatia:

Can I just add for that Lily, because that kōrero there you just talked about, sometimes it’s sharing that you’re vulnerable with your child is it can be a real challenge, because you’re supposed to be this perfect person, this human being who’s adult now knows how to work things out, our love. I just want to acknowledge that. I do the same, and with my kids I said, “Look, can we start again. I’m sorry, let’s start again? I was a bit of in a rush. You understand that I’m under pressure etc. So can we start again?” Our kids are very forgiving, and some, not straight away but they are very forgiving.

Lily Chalmers:

Yeah, we’re very lucky and every day is a new day isn’t it.

Jason Tiatia:

Yeah, awesome.

Lily Chalmers:

Yeah, absolutely, wonderful. Oh, that’s such a good kōrero. Thank you, and I just wanted to talk about the six principles in action. So we’ll come back to you Lynette. What do the six principles look like in your mahi right now, and how do you use them?

Lynette Archer:

We realise that the six principles work well for everybody. We work with a variety of parents but we also, with the Tākai funding, are alongside grandparents raising their mokopuna, here in Whanganui, and that’s been a really big part now of our initiative, that feels like it’s snowballing but we’re learning a lot. And I’m thinking about what it feels like for that next generation on. I know myself, as a nan, that I’m watching my children parent different to how I parented. And so, these grandparents that are coming in, they are really thinking about how it feels to be doing something that’s really different for them. So the first thing with the six principles that we use is that whole love and warmth. We try and make sure that the space that they first connect us with, is really loving and warm; has a cuppa, has kai if we need it, and is a space just for them. So we try not to do it in a crowded space, or a space where they feel like someone else is listening because that’s really important. Their stories are really big, as are parents who are finding life a little bit hard at the moment.

So that’s really important in terms of that initial thing, and then talking and listening well. We’re fortunate in our initiatives here that we don’t have a timeframe for people. We haven’t got hourly appointments, or they can come in and if it needs to take two hours, or a whole morning, that’s what it can do, as long as we’ve got the capacity.

So, we’ve discovered that listening is a very powerful tool for parents, and grandparents, and it just gives them the power actually. It’s not for us that, it empowers them to know that their story is really important. And, as we listen, we can guide them and help them to work out what their understanding their needs might be. So, if you can see, we kind of follow that cyclical model, realising that actually the importance of how that comes, to then, how they can look at their own limits and boundaries around, what feels safe for them, and not just diving in, thinking they’ve got to make difference to everything, but just letting their world unsettle in kind places, with support if they need it, or just a bit of awhi, to carry on and try something new, to see if that helps. I’m sort of thinking that for us, is the simplicity of the six principle model, and we’ve seen it in action and we know that we’ve had some really lovely outcomes, with whānau.

We’ve watched it making such a difference to the tamariki, because the parents and grandparents suddenly feel like their needs are being heard, and they’ve been given the support to try some things, that maybe they hadn’t thought of, but by just being able to unpack it well, they’ve picked out things that could make the biggest difference first.

Lily Chalmers:

That’s amazing.

Lynette Archer:

That kind of answer that?

Lily Chalmers:

Oh yes, and what a beautiful space to be in, and I think that’s a lovely thing to remember, is that just giving them the space and the time, and that flows onto them giving the space and time to the young people, to the tamaiti, that they are caring for as well. What you’re doing is flowing onto to how they are practicing, and their parenting and I just love that. You did mention parents having tricky times, and I wanted to just ask you, what does that look like, how do we talk about love and warmth with families that are experiencing tricky times, and by tricky times there might be some violence in the home, or some other real stressful issues that are really crushing down on that whānau. So, how do we talk about love and warmth, when there is that stress at home?

Lynette Archer:

I think one of the early parts of that is asking what they’re doing for themselves, because we can’t function out of an empty bottle. So, love and warmth is about looking after ourselves, as it is as much looking after others, and if they’re feeling; well, supported is not the best word, but if they’re feeling they’ve got a place where they can just come and be themselves, and they’re accepted, there’s no judgment, there’s no rules, there’s just that safe space. So, if there’s something comes up that we’ve got to be careful about, we know how to have that next conversation, but for them, sometimes they only ever feel judged.

So when you’re in a hard space you feel like everybody knows; everybody knows you’re doing a stink job as a parent, everybody knows that your kids are misbehaving because actually what’s happening in your world is not good. So we begin there. We begin with how do you fill up those tanks first, and then asking them, “What do their kids love doing?” Extend it out, so that they think about, ‘what does it feel like to have fun in our house, and what could we do one thing this week that feels like we’re having fun together’, because that’s giving love, and filling up our love tanks.

Lily Chalmers:

Oh beautiful, yeah, and it can be just one thing can’t it.

Lynette Archer:

Yeah, and it generally doesn’t stop at one thing. Generally there’s something they think, ‘oh, we’ve done this let’s try this next door’. “Remember when we go to the beach mum, how we just love digging holes.” There’s such therapy in digging a hole to China.

Lily Chalmers:

Absolutely, and the simplicity of it, that’s what I love about it. If we just focus back on these small things we can build those strengths gradually and build up our resilience as parents, and then maybe that will give us the resilience to go a bit wider, and deal with some of those trickier issues that are happening in our homes. Thanks, that’s wonderful.

Jason, what do these principles look like in Pacific cultures, and what do you see whānau doing really well?

Jason Tiatia:

I think our Pacific are very beautiful in a way we’re collective. We’re very community type of people, and definitely we want to be individuals when we need to, but generally we very much come together as a whānau, or aiga we like to call in our Samoan language. And just bringing up Anna’s point where the discipline, the word ‘discipline’ itself. We use the word a’ava or usita’i, which are the words like obey, and also respect. Those are the big pillars for us, in terms of the fa’aaloalo, which is the respectful side and giving dignity to our elders, and serving them in a way where we just love to. And the other side is when you get older the adolescent brain tends to sometimes go off track of course, and that’s just part of the growing up, and we have to reconnect them back to these values of love, care, respect, and being kind, etc. But all the values that we have in terms of the six principles that we’ve been listening to, they coincide and they align to our Pacific values too. They’re a huge part in our community.

I think without our generation before, that have set the platforms and a really good foundation, and now it’s really up to us who are the parents of today, to actually teach and share some of that knowledge as well. Culture and language, now identity, those are huge things for us. So we need to continue the being bilingual, being trilingual in most cases, some cases. Around the world there’s probably we’re a little bit behind of course, in terms of being bilingual, but the most of the rest of the world, or most of the world are the more bilingual rather than monolingual. I think that’s a big key part for Aotearoa, living here, is that we need to continue to learn te reo, and we respect the culture that goes with that too, and I think that’s a really important part as Pacific, because we’re the cousins, we’re the teina here, and we respect the people of the land.

That’s a big part in terms of Pacific, and then we lead with that when whatever we do. Some people think it’s a vulnerable part or it’s a weakness of ours, but I think it’s showing humility right from the start. We always bow when we past people, and we teach kids, “Hey, put your head down when you go past people.” “Hey, say excuse me, say tulou, say tulou.” I think those are the things that we need to continue as adults to keep practicing with our kids, and our kids always keep us honest as well, but ultimately, food is a big one and food is massive, right, in our culture. I think that’s a universal thing but particularly in Pacific cultures, and we love sharing food, and when we host we definitely host, and you’ve got to eat everything on the table, even though you’re full, twice. But it’s one of those things that we have to continue to do, and we love sharing food and that’s a big part to have in your family.

And then the last thing is Pacific dads. Our dads are supposed to be this master in the house, but we know being a modern dad these days we’re the stay-home-dad, or the parent. We have to be more innovative and more creative, and even just breathing, just breathe when things go pear-shaped. For me, sometimes I had this trigger, and how my parents parented me, I’m like, “Āe!” I’m a bit harsh, and my wife keeps her eye on it, “Hey, breathe, and walk away and then come back and deal with that issue.” “Alright, alright, alright.” It’s a really important part as fathers of the world. When you’re there, set a role model; what we want to see from kids too. So that’s something that Pacific need to continue to do.

Lily Chalmers:

Oh, I love that, and I like how you said we’ve got to bow; you tell your kids to bow when you see someone to show respect, but you’re not just doing that in isolation, you’re doing it with the talking and listening and you’re giving them that guidance. It’s not just do what I say, it’s like this is why we do this. This is why this is important to us because it’s part of our culture, and making all those links so that they understand I’m not just doing it because you tell me to, because you’re the boss. But there’s a reason behind all the ways that we do these things, right.

Jason Tiatia:

I love you how you said it’s the why, and these days, “But why?” Because back in the day we used to ask, “But why?” “Just do it, just do it.”

Lily Chalmers:

Exactly.

Jason Tiatia:

“I want to know why.” I think that’s the important communicating in a way the kids understand the simple language that Lynette talked about, and just keeping it simple. We don’t have to complicate things too much and give them the whole encyclopaedia of a definition, but say, “Look, this is the why in terms of our values, etc, etc.” And what family values mean. So that’s it, it’s a really key part; so the why is a good one.

Lily Chalmers:

Awesome, and you also mentioned thinking about how your parents parented you. I mean, that’s something that’s very hard to get away from sometimes. As a parent we just automatically go into that system that we were born into, but I wanted to ask you Anna, how do we guide whānau to understand how they parent, and so, they could be conscious about maybe making those changes?

Anna Mowat:

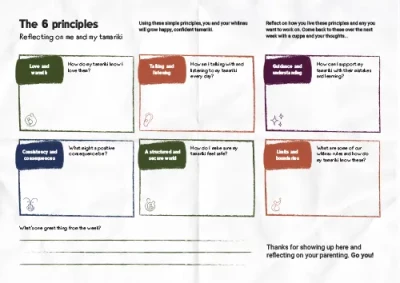

One of the nice things about the six principles is they don’t require any kind of training or course or book that goes with them. They’re kind of imminently available for everybody, and sometimes it’s nice to offer them to parents. Though, sometimes when I’m working with parents, I work with them; I’m solely there to work with them about parenting. So, you get to offer these things and ask them about, “Which of these do they think they want to work on, or isn’t so apparent?” There’ll be some that are beautifully apparent and some that aren’t so much, and then they might say that that might be around limits and boundaries, and then you talk about, “Well, what does that look like? What was that like for you growing up, or tell me about your memories of limits and boundaries.” And then you get the story, and you get sometimes the pain; sometimes the deep joy, and you get to discuss what it is that they want to bring with them, and keep while they’re parenting today, and what is it that they want to leave behind.

Then they get to define these things for them, their family āinga, and what that looks like, feels like. I guess that’s one of the ways. It’s also a way that you work with tamariki, like these are things that keep us really happy and really safe, and what are the things that are really available. What do mum, dad, grandma make really available to them here, and have them hear that. Have whānau hear that as well, and then also, “What are the things that you’d like to see more of, inside of this family here?”

Lily Chalmers:

Oh, I love that. Yeah, so it could be a conversation you have around the table, weekly family meeting, and maybe getting some feedback from your kids about what you’re doing well, just like in a job situation you do that annually, don’t you, and doing it regularly with your kids saying, “I don’t know if I want to hear the answer to this, but what am I doing well, what do you think I need to work on?”

Jason Tiatia:

We do that particular part, and during prayer. We close the night with a quick prayer, and we’re going to say, “Hey, what’s one thing we can work on, what one thing that we’re awesome at.” It’s funny because the siblings sort of go, “Mm hm whatever, whatever, you didn’t do that, you didn’t do that.” But which is cool, and it sort of keeps people honest and accountable to the family, and it’s a great way to share aspirations too. I think it’s a big part, and using part of your brain, in terms of imagination or big picture stuff, and that’s part of the strategy, “If you want to head there, these are the three things; you need to work hard, you need to get up early, etc.” And just those basics. We’ve always heard the term around ‘making your bed’. Make your bed, and that’s the first call, and then you can actually achieve in lots of things. I think myelinating that part in terms of individualism is empowering for self-belief, self-care, and obviously, our wellbeing.

That’s really what Brainwave is about, and just sharing that information that we’re doing some really awesome things, continuing, and push aside some of those other things, those bad habits, the best you can, and that’s around just a practice, it doesn’t happen overnight that’s for sure. So keep practicing.

Lily Chalmers:

I guess that’s one of the things we talk about in the six principles is focus on the good things; praise the good things, maybe ignore some of those bad things. Although, some of those things that trigger, and as you say, have a bit of a deep breath and focus on something else.

I wanted to go back to six principles, our whānau tikanga just for a minute, and ask each one of you is there a principle that particularly sticks out to you, or really resonates with you, and I’m sure you love them all but is there something that is your fav, have you got a favourite that you’d like to talk about briefly, and we’ll start with Lynette.

Lynette Archer:

I always think about guidance and understanding. I think understanding comes before guidance personally, but often times we don’t take the time to really understand what is on top. We do that with our tamariki, we do that with each other. But if we just take that little bit more time, understand what’s on top, and then together we can strategize. We can guide to something that might be helpful, and I think it we could all take time to do that, with love and warmth, by listening carefully and talking together well, it just makes such a difference for everybody.

So that’s where maybe I’m a strategist person but I believe that makes the biggest difference in my world, and with those around me.

Lily Chalmers:

Beautiful, what about you Jason, do you have a favourite?

Jason Tiatia:

Yeah, I was just looking at that six there, but I think for me is the consistency and consequences. I’m generally coming from a sporting background, to being an ex-professional rugby player and then coming into this world of education and I’m sharing the facts around neuroscience. I reckon it’s the coaching part where you’ve got to be consistent at being good at something, and then there’s obviously consequences when you don’t do it, and just understand that that’s the part that our kids can’t be always feeling good about things, and when challenges arise; we can give them some strategies or ease some of that pain just through chatting, or just being still sometimes being in the room with them.

I know I’ve shared a couple of experiences about my kids, but sometimes my son, who’s thirteen years old or just turned fourteen; he doesn’t speak much. I’ve sat in the room, took about half an hour and then he said, “Yeah, had a really good day dad.” I’m like, “Whoa, okay why didn’t you say that right at the start because I thought there was something wrong.” I think just being still and understanding that consistency around your kids, each ones different, and also some of the consequences that they might face when things don’t go right. I think that’s a big part for me, just being one, a dad, but also understanding how the brain works.

So, if you’re out there, get some good, really good structure with your routines, and with your kids, and then obviously there’s time to be unstructured to where it’s spontaneous and that’s a beautiful thing, but being spontaneous every day can be disruptive and can be a bit chaotic, but I think our kids today, especially today’s world where they’re dealing with so many other moving parts, just try and be consistent the best you can.

Lily Chalmers:

Awesome, and of course consequences aren’t always negative. There can be positive consequences about the great things that do, right.

Jason Tiatia:

Yeah, that’s right. Yeah, there’s really good outcomes when you do, do something, and then all of a sudden an opportunity arises. So those are really cool things about it too.

Lily Chalmers:

Do you have a favourite there Anna?

Anna Mowat:

Oh, I do love them all. I’m pleased that you picked up consequences because that’s another word that we misinterpret is only being negative consequences, but of course praise is a consequence as well. But I always go back to ‘love and warmth’ if I’m writing any material for parents, or kaiako. I always think about, ‘how will these people know that I truly respect them, and just love what they do’, and I always think about that, when I’m on the doorstep of somebody new that I’m going to be working with, and I’m knocking on the door, ‘how are they going to know that I really respect them, and that I’m only wanting to see their strengths’. So, those are some of the things that I yeah, bring with me.

The other thing is too, just going back to some of the stuff that Lynette and Jason have so beautifully said, is it’s often a whānau in stressful situations because they don’t have enough of this available to them, or they don’t have, it’s openingly apparent in many of the environments that they walk across. So, if we can bring that to them, or we can advocate that that’s available for them by even introducing them to other community members, groups, etc., that always have their six principles available, they’re always welcome. I mean, Woven Whānau’s a beautiful example of that; don’t we all want to go and sit in Lynette’s space.

So, having this more available for our whānau, means that they’re only going to learn from it and understand it more and bring it through into their worlds and lives, and to their children.

Lily Chalmers:

Gorgeous, lovely. Oh, that’s so wonderful. I wish we could keep going on for ages and ages because there is so much to talk about and I really enjoy hearing all your kōrero, but we do have to go to our Q & A, and we’ve got a few questions in there already. Lamberta asked: What are some of the disciplines that you can recommend?

So I guess that’s thinking about some of the actions you might take to teach your children. Does anyone want to jump in, and answer that?

Lynette Archer:

I think that comes down to understanding what the need of each child looks like, and what things need to be consistently in place. I always tell the story that if you were to ask a child what a consequence is for something that they do wrong. They are often more harsh, those consequences that they would say, than we would give them ourselves. So we’ve got to be really careful, like we talk about consequences are also positive; catch our children doing good things, and I think that’s a really big part of how we can support what discipline might need to look like in our family. What do good things look like in this family wee stuff; we talk to each other kindly; we respect each other’s spaces. Discipline isn’t about putting stuff in place to make change, it’s about growing together, and finding out how we live in harmony. That’s my two cents worth in there if that’s helpful.

Lily Chalmers:

Oh, I love that, and it works quite well too, when if you’ve got more than one child, if you catch one child doing something good, and you’re saying, “Oh, I love how you are being gentle with the cat.” And then quickly someone else wants to try and do that, and see if they get the praise as well. It has a flow-on effect with the other tamariki doesn’t it.

Jason Tiatia:

Well, I actually do that too. When I hear someone giving a compliment I’m like, ‘oh yeah hey look at me, I need to do something quickly’. So even as an adult right, that’s a motivational tool, or strategy too. I think it’s not just the kids, it’s all the way through, and definitely the words, and that environment that we set helps. It’s the law of attraction I guess.

Anna Mowat:

We are social beings aren’t we, we love to be around people and we love to get their understanding and we love to hear that they like being around us. We don’t often talk about praise as a strategy, and actually we can change behaviour using praise but we just need to shift our focus to it. So really strong way to actually really focus in on some of the behaviours that we want to see more of, and strengthen those rather than wholly looking at the things that we want to change.

Jason Tiatia:

And just to add quickly, in terms of the neuroscience behind it too. Now, the thing called the Hippocampus, in your brain. It’s the memory bank. That’s where lots of our awesome memories are held, but also not so good ones. There can be really explicit memories, or implicit. It’s a really hard one to explain sometimes because I can feel something, I don’t know why. So if they have a good feeling all around in the house, slamming doors is probably not good. So those sort of things, and there’s got to be gentle ways to sort of give really good experiences too.

The last thing I want to share about the neuroscience is around the Amygdala, and that Amygdala part is around I guess the smoke alarm. So when there’s something, a stress or something’s in fear or they could feel something’s not right, or they can see, they don’t even need to be in the room, sometimes it’s just the feeling they have in that space. So giving them those beautiful spaces experiences does help them when they’re an adult, they become better decision makers, change agents, etc. I think that’s a really important part too. So thank you.

Lily Chalmers:

Great, we’ve got time for one more question from Anthony from Talking Matters. Kia ora Anthony. He asks: If you have a household that has more than one parenting and or caregiving style around tamariki, houses of ten people etc., how would we kōrero with whānau around that? Sometimes whānau clash when it comes to disciplining tamariki, and I think that’s a really good question. Who would like to jump into that?

Anna Mowat:

I’m really happy to make a start. I mean, I think those six tohu are a beautiful place to start, including something along the lines of, “I was on this webinar today, and there’s lots of research around these six things, and what do they mean to us or how can we have them all available between us, and with our tamariki.” You start the kōrero in that way because it might not be about different styles, it might just be about different understandings, and sometimes we get lost in the busyness and the stress of our lives. I mean, I keep going back to the six principles don’t require any training or a parenting programme around them, or anything like that. They just require us to really think hard, and focus on our relationships, and when we’re able to do that in these kind of positive ways, sometimes we can let go of the stuff that doesn’t quite kind of sit the way that we would do things. I mean, hello, our guidance and understanding shows us that, tells us that.

Jason Tiatia:

For me and being sometimes in a bigger family it is a real challenge. I think what needs to happen is; well, for us, from what I’ve experienced in my community and my family, it’s just really being kind, leading with kindness. I think that’s a big one because like we said there’s different I guess, we have the same values but interpreted differently, and that’s the understanding of it. I think with my dad and my mum in the house, in my house; we tend to clash, or like, “Hey, don’t do it that way.” “Hey, hold on, me and my wife have got this agreement.” So we’ve got to clear that space a little bit more before we get to the kids. It’s just a matter of communication, and working through those challenges, and it will take time. So, just hang in there and be patient, be kind, and it will work out.

Lynette Archer:

I was just going to put in quickly, because I’m māmā to six tamariki, and I was grateful I got them one at a time. I learnt the nature of each of those children before the next one came, and it taught us a lot about our own relationship, my husband and I. We began to be able to understand how we felt about when certain things happened. I just want to tautoko what you said Jason, about relationship and communication. It’s huge but generally, if we understand the needs of each of our children alongside that, it does help how we parent them and how we bring our styles together.

Anna Mowat:

I think you’ve said it, and it’s okay to disagree. It’s okay to have different ways of coming about things, and the way that you work through that is beautiful modelling for our children, if we can as Jason says, focus in on that relationship, and that you actually all love each other. Our children are learning from that too; I think that’s the greatest way that they’re learning.

Lily Chalmers:

Great, we do have one more question; I wonder if we can quickly broach it. It’s quite a biggie so we’ll give it a go. Lizzie asks; What can we say to rangatahi Pacifica who tell us that physical discipline, a hiding, is normal?

Jason Tiatia:

I’ll quickly share my view on that one. I think it’s not normal, it’s because they were taught that way, the last generation even before that, but I know my grandparents; man, they were beautiful people, and it is not until my parents were influenced differently too. I think it’s not a cultural thing as in like it’s Samoan, or Pacific, it was a worldwide thing at that time too. I think we have to change the narrative there, and say, “This is how Samoans raise our kids.” “This is how Māori raise our kids now.” Let’s leave that behind, because I think we can’t change that part but what we can do is change our mindset to move forward now, because we’re beautiful people. We need to show that, and we can’t using our hands, we have to use our minds, and the words that we give our kids.

The last thing is mana; kids have mana right from the start. I’ve learnt that from Māori; they had mana. We need to continue to give them the mana, and raise them up, praise them, encourage them. We need to equally share our respect too, for them and with them.

Lily Chalmers:

Brilliant, and I think that’s an opportunity to talk about colonisation. You’re got a rangatahi there. You can have a really good strong conversation about what the colonisers brought with them, and how they felt that they had to control the people that they came across, and how that’s not okay; how we know better now, and we’re trying to undo some of that, and we’re all part of that aren’t we.

What a beautiful kōrero. Part of Tākai Kōrero, we do want to share some of the resources that we have, that can help you work with whānau, and can help whānau out there in communities. We’ll start with our amazing Whakatipu booklets, and Ngā Tohu Whānau is woven through all our Whakatipu, and our Tākai resources. In this one for example, Te Pihinga, is from seven to twelve months, and it has some really great activities about using ngā tohu whānau with babies, being consistent, saying “kia tūpato” when baby’s heading towards a danger, that’s a structure and secured world; copying baby’s noises, talking and listening, and giving them activities that are right for their age and stage, guidance and understanding.

Our next wonderful resource, rauemi, is Sparklers at Home. Sparklers is for teachers but then the section on the website, that’s for parents, and Sparklers at Home is a great place to send whānau you’re working with. They share a lot of activities that are all about having fun, and enjoying your time with kids, and there’s a great resource there about, just having fun and enjoying your time. And lastly, our baby wall frieze. I mentioned it earlier, you can order it off the Tākai website, from our resources page; free to order, and it does come in Samoan and Cook Island and English and Te reo Māori. It’s a great resource, shows simple things that you can do with babies. We can use it at all ages and stages as we mentioned before, even with ourselves, with our partners, with our workmates.

So, thank you so much for tuning into this Tākai Kōrero session. Thank you to all the wonderful kāikōrero who have shared. Lynette, Anna, and Jason, thank you so much, it’s been such a rich conversation.

We’ll be back in September; Wednesday the 21st of September at 10am, with a ruku workshop. There’s a hundred spaces for that and we’re going to put a link in the chat now. So you can sign up, and that’s a deep dive into the kaupapa, what we talked about today, and we’ll talk with other whānau supporters, build connections, and share your ideas and get some ideas of other people. And, please, remember there’s lots of free rauemi, tips and advice on the Tākai website: takai.nz.

Mā te wā, we’ll see you at our next Tākai Kōrero. Thank you everyone.

Kaikōrero

Lynette Archer, Woven Whānau Wanganui

Lynette is the coordinator for Woven Whānau Whanganui, an initiative funded by Tākai that was previously known as SKIP Whanganui. Lynette began walking alongside families when hosting playgroups and has always been passionate about seeing whānau and tamariki able to be the best they can be. Lynette loves the Woven Whānau philosophy of all whānau in Whanganui reaching their full potential to love, nurture and care for each other, extending to those around them.

Jason Tiatia, Brainwave Trust Aotearoa

Based in Christchurch, Jason Tiatia is a Brainwave Trust Aotearoa kaiako . He's also a programme coordinator and tutor at Ara Institute of Canterbury where he teaches sports coaching and indigenous studies, tutors in pacific performing arts and Gagana Sāmoa. Jason represented New Zealand in the All Blacks rugby sevens spent time playing in several countries and has been a selector and coach in the Canterbury region

Anna Mowat, Real Collective

Anna works across many Aotearoa initiatives and projects that support tamariki and whānau. She is the project lead for Sparklers, directs Real Parents and has been using the 6 tikanga in her mahi with whānau and as a parent for the past 16 years. She is clinically trained in psychology with a predominant focus on tamariki wellbeing.