Challenging behaviour

Every child pushes boundaries as part of learning to get along, but sometimes challenging behaviour is caused by wider problems and trauma.

‘If children have warm, trusting, responsive and reciprocal relationships with their caregivers they are likely to develop internal controls on behaviour, and learn what their caregivers want to teach them. If children experience criticism, lack of acceptance, and feel unloved, they are likely to become defiant and aggressive.’

— Children’s Issues Centre, 2004

Learning to be a ‘good enough’ human

No child is born with a blueprint all set to grow up perfectly socialised into their family and culture with all the appropriate behaviours intact. There’s a lot of learning to be done, and there can be many hiccups along the way.

Learning to be a ‘good enough’ human being is a complex activity with many factors involved – a person’s internal genetic makeup, temperament, outside influences over which the family has little or no control, and most significantly, what happens between the child and their whānau.

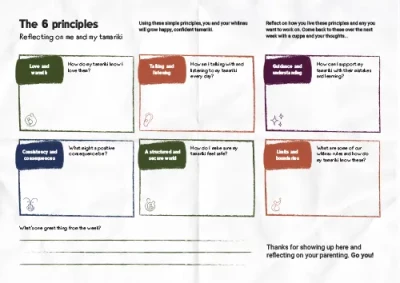

References to the ‘Six principles’, also known as ngā tohu whānau, occur throughout the Tākai resources. Why? To continually remind us that the 6 principles are the foundation of every aspect of parenting – which is the thing that happens between parents and their children. Tākai calls the 6 principles, ‘The 6 things children need to grow up to be happy, confident adults.’

The foundation of child development is a healthy, well-regulated brain. Thinking and emotion can work well in tandem. When we experience stress, our brain can get us back to a steady state.

When things go wrong

What happens when things go wrong – when the 6 principles are lacking? There are lots of ways that might happen. Remember that no one gets it 100% right – what we hope for kids is to get ‘good enough’ parenting.

But sometimes things can go very wrong. How might that happen? Let’s imagine a continuum along which children’s behaviour and development sits. A large portion of that continuum falls within a ‘normal’ range. All kids need to test the limits, all parents have areas that they struggle with or have not yet addressed.

And then there are the more severe instances, such as families in serious stress, adverse conditions that traumatise the family and the children, situations of abuse and neglect, times when children have been removed from their parents and placed with other carers – sometimes whānau, sometimes with strangers.

At the extreme end of the continuum, children can become very distressed. The effect of the trauma they’ve experienced can influence their:

- behaviour

- ability to learn

- emotional, physical, cognitive and language development

- trust in the world and all the people they encounter.

Love and warmth

One of the most important things that all children need from their parents, whānau and caregivers is feeling they’re loved. Ongoing loving relationships make it more likely that tamariki will accept parental messages.

What leads to a lack of love and warmth?

This can happen through:

- an insecure attachment

- loss of an attachment figure

- the child being removed from their home

- parental depression

- parental neglect or abuse

- parents’ own negative history

- unhelpful beliefs, like thinking you can spoil a baby by showing too much affection.

What happens to kids who don’t get love and warmth?

Not experiencing enough love and warmth can make a child:

- feel unwanted

- unable to trust anyone

- miss out on opportunities to learn self-regulation and empathy

- unable to develop internal controls.

These children are more likely to:

- be defiant

- be aggressive

- have a negative self-concept and negative feelings

- have conduct problems

- have anxiety and depression.

Kids have told Tākai researchers that they want the adults around them to:

- help them have a good heart

- be friendly

- do fun things

- kiss and cuddle them when they’re upset

- comfort them

- use a happy voice.

Repairing a previous lack of love and warmth

Parents and caregivers can help by:

- knowing that the child needs them to be calm and understanding

- remembering that the child is not ‘naughty’

- engaging and connecting with them to build trust or help them to regain calm

- doing kind and helpful things with them like tending their accidents carefully

- giving them full attention, hugs and cuddles, and saying encouraging things to them.

How does playing together help?

A key tool for parents and caregivers to repair or reinstate the 6 principles is through play and activities. There is such value to be gained and enjoyment to be had through playing together, having fun and sharing attention.

It’s also such an important way for the adults in the child’s life to strengthen their relationship and use the 6 principles to lay down the foundations for behaviour and learning.

This may be particularly relevant for foster carers or whānau caring for a child who has been taken away from their parents, to help to build their relationship and strengthen engagement.

Trauma-informed care

Although designed for whānau supporters, anyone can register for the free eLearning course called Trauma-informed care for the children’s workforce(external link).

How do you support the parents or carers in acute situations?

The basic information in the Tākai resources still applies, as will the resources:

- The 6 principles

- 'Conscious parenting' booklets

- The baby frieze

- The Whakatipu booklets

- ‘Aroha in action’ booklet

These resources provide parents and caregivers with all of the basic tools.

Living with children who are traumatised involves re-establishing basic positive parenting strategies, and requires mindfulness, understanding and calm. The ‘Staying calm with kids’ booklet and fridge magnet may be very helpful in these situations.