Whakapapa – He kākano au

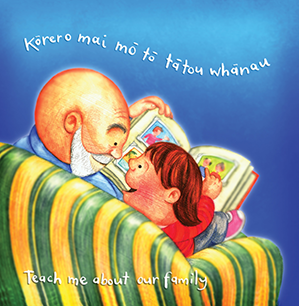

Experiences like sharing photos to talk about whakapapa let pēpi know that they belong and are connected with other people. Repeat whakapapa names and stories often so pēpi will remember them.

He kākano au i ruia mai i Rangiātea.

A fuller version of this whakataukī is:

E kore au e ngaro, he kākano i ruia mai i Rangiātea.

I will never be lost, the seed was sown in Rangiātea.

How pēpi can learn their whakapapa

At a simple level, whakapapa starts with pēpi and the people they see regularly. Whānau can use words like:

- tuakana

- teina

- tungāne

- tuahine

- koro

- kuia

- whaea

- mātua

- mātāmua

- pōtiki .

You could show whānau this interactive tool. You hover the mouse over one family member and it shows the words for the relationship the others have to that person.

Terms for family members | Te Ara(external link)

Using photos of family members to share whakapapa works well. Photos might be in albums or boxes, on walls, or in an electronic format. The format doesn’t matter. The key is making reference to them regularly. Starting early and enjoying these photos together can be a much repeated and enjoyed experience. More whānau stories can be added over time.

A whakapapa tree is a useful tool. You could ask whānau whether they’d like to try to create one for their tamaiti.

Early experiences like these let pēpi know that they belong to, and are connected with, other people. They belong to a group – a whānau, a hapū and an iwi. Growing up secure in the knowledge that they belong in the world is an important factor in promoting wellbeing and resilience.

Whānau support and connection

Support and connection are very important protective factors in building resilience. Dislocation from family and roots is a risk factor. Whānau support workers can help young isolated parents find appropriate social supports. They can also encourage them to find and strengthen whānau links, not just as a support system, but to build a sense of belonging – mana whenua. Feeling confident in who we are and how we cope with the world now is to some degree dependent on knowing where we’re from and from whom we’re descended.

The most successful social services often put energy and time into helping young parents find their roots – both living relatives and past history. Knowing one’s whakapapa can put lives into perspective, and give a secure footing in the world.

Engage whānau in telling their stories

Every whānau has a different story about whakapapa. Engage whānau in telling their stories. Some will be knowledgeable and open, but others may be disconnected and unsure. Remember not to assume anything. There will be many ways to talk with whānau about this topic.

If parents are disconnected from their roots, you might tactfully ask how they would feel about making contact with whānau, and what help might be needed for that to happen. Respect their wishes. They may have their own reasons not to want to be reunited with whānau. Āta haere – tread softly.

Conversation ideas

Helpful resources for whānau

-

Whakapapa

National Library of New Zealand

A guide on whakapapa research resources available online from the National Library of New Zealand and elsewhere.